What Would Happen if Something Happened to Your Drinking Water Supply?

Prepared by Andrew Stone, Hydrogeologist (andrewstonewater(at)gmail.com)

A “Sole Source Aquifer” (SSA) refers to a groundwater source (aquifer) that is a main source of drinking water for a designated area. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines a SSA as an aquifer supplying at least 50% of the drinking water consumed in the area overlying the aquifer. Sometimes the boundaries of the SSA include recharge areas that may lie beyond the actual aquifer. SSA designation is intended to protect drinking water supplies from overuse and contamination. There are regulations and land-use restrictions for SSA zones to reduce risks of the loss of water source inventory.

The declaration of a SSA is particularly important where losing an aquifer because of contamination could lead to negative economic consequences and huge engineering costs to bring in a replacement safe alternative water supply. The EPA has authority under the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act to determine SSAs. There are 76 Federally designated SSAs in the USA. Some examples are: Eastern Snake River Plain (ID), New Jersey Coastal Plain,(NJ), Cape Cod, Nantucket & Martha’s Vineyard, (MA), Long Island, (NY), Edwards Aquifer,(TX), Biscayne Aquifer, (FL), Dayton Buried Valley, (OH), Tucson – Santa Cruz & Avra Basin, (AZ), Columbia and Yorktown Aquifer, (MD).

In addition, tens of thousands of communities have source water protection regulations for drinking water. “Watershed protection” road signs serve to remind citizens about the value of safe dependable drinking water. Here is brief background information about just four SSAs with links to more information.

Dayton, OH

A buried valley filled with glacial sediments is the sole source aquifer system that serves over 1.5 million people in the Dayton Ohio area. The sands and gravels deposited by meltwater from glaciers over 10,000 years ago are in some places 300 feet thick. Over much of the valley-fill aquifer the water table is close to the surface, making it vulnerable to the risk of surface contamination.

Edwards Aquifer, TX

The Edwards Aquifer is the source of water for about two million people in Texas, including the city of San Antonio. Artesian wells, and the springs where water emerges from the aquifer are vital for drinking water supply and ecology. The aquifer is made up of porous and permeable limestones that reach depths of 300 to 700 feet. The limestones are broken by faults and joints, making the aquifer recharge zone vulnerable to contamination. Because of regional tilting of the rocks millions of years ago, the limestones are exposed at the surface in some places (recharge zones) and in others are buried beneath layers of sediments (artesian zones).

Cape Cod Aquifer, MA

The aquifers of Cape Cod and the islands are comprised of sand and gravel deposits left behind by melting glaciers 15,000 to 20,000 years ago. The glacial sediments range in depth between 200 and 600 feet. The aquifers are recharged by rain and snowmelt, and because the sediments are permeable there are very few rivers or streams. Provided that there is not too much pumping, rainfall recharge maintains a “mound” of fresh groundwater that prevents seawater from migrating to inland wells. Managing SSAs in coastal areas involves closely monitoring water quality and restricting pumping in times of drought.

Cape Cod Aquifer, MA

This SSA covers over 10,000 square miles in Idaho between Wyoming and Oregon. The main aquifer comprises volcanic basalt rocks recharged by precipitation and surface steams. Because of past overuse by pumping, the whole aquifer is now carefully managed to increase recharge and reduce pumping. Sustainable irrigation for agriculture is of great economic importance, and the aquifer is also the sole source of drinking water for 300,000 people in eastern Idaho.

How About Walking Down to the Bottom of a Well With Your Bucket to Fetch Water?

Prepared by Andrew Stone, Hydrogeologist (andrewstonewater(at)gmail.com)

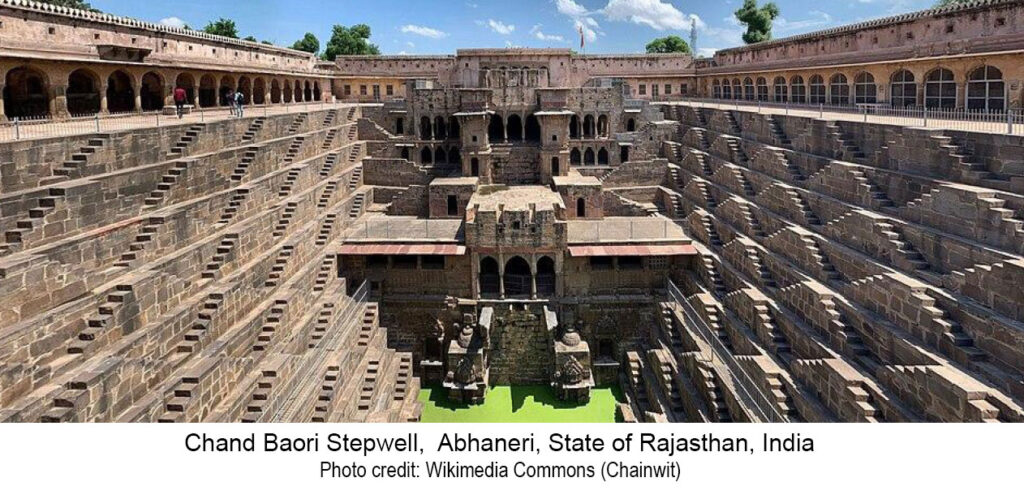

Did you know that there are over 3,000 stepwells in India with many others in arid countries? Water wells are typically constructed or drilled as simple vertical shafts. However, a stepwell is a large diameter excavation constructed to reach permanent groundwater. Access to the wellwater is via a series of stone steps down from the surface to the well water. At a time of low groundwater, it takes several staircases of steps down to reach the water level.

Locally known in India as baoli, the primary purpose of stepwells is to provide year-round availability for water, especially in arid and seasonally arid areas. To make groundwater available year-round stepwells are excavated to a depth just below the lowest expected groundwater level (water table). Steps in a series

of staircases allow people to walk down to reach the water. As the groundwater level rises in the well,

(in India, often as a result of seasonal monsoon rains) the lower steps become submerged and less staircases are used to reach the water.

The picture above shows the 100 ft deep Chand Baori stepwell. (The green color is the water!). The well was constructed in the 8th and 9th century and has a total of 3,500 steps in thirteen levels of stone staircases.

The picture on the left is of the 15th/16th century stepwell called Ujala. It has a less-complex design than Chand Baroi but operates on the same principle.

Stepwells had the primary secular purpose to supply water. However, over the centuries many took on additional significance that led to elaborate architecture and carvings to honor different religions and to give recognition to the dynasties and sultan rulers who financed the stepwell projects.

Still on the subject of history, during the 19th century when India was part of the British Empire, stepwells were decreed by colonial authorities to be unhealthy, and water supply was provided by drilled wells. Many stepwells were then closed and some were filled in, fell into disrepair or became dumps.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and with increasing population, increasing aridity and monsoonrain uncertainty, water managers in India have to consider all options. Many stepwells in India are now being cleaned out and recommissioned to augment supply sources. For example, groundwater is now restored as a supply source at stepwells in Jodhpur (Toorji ka jhalra stepwell) and in Rajasthan, (Moosi Rani Sagar stepwell).

Search the web for many sources of more information about these fascinating constructions that access groundwater. Wikipedia is a good starting point. Also, visit Stepwell Atlas for an interactive map of world stepwells. [Note – the two stepwells listed in the United States don’t function as traditional stepwells!]

In the age of steam locomotives in the US, from the mid 19th to the mid 20th century, water was a critical need. The availability of water from springs was often a determining factor influencing routes of railroads in desert environments. Surveyors seeking water sources often worked years ahead of rail line construction because routes had to follow water availability. Steam locomotives could use up to 150 gallons of water per mile and required frequent stops to “fill-up.”

Bonanza Spring is the largest spring in California’s Mojave Desert. Located in the foothills of the Clipper Mountains it emerges from bedrock as a perched spring disconnected from the basin-fill aquifer systems in the desert valleys hundreds of feet below. The spring is at an elevation of 2,105 feet above sea level. According to historical records, and current measurements, the spring flows at a fairly constant rate of about 10 gallons per minute. In stark contrast to the dry surrounding landscape, vegetation where the spring emerges (photo) includes mesquite, cottonwood trees, and cattails. In addition to serving as a water source for creatures such as desert bighorn sheep, desert tortoises and jackrabbits, the spring is habitat for frogs, toads, catfish and bluegills. (Separated from the nearest permanent surface water sources by many miles and great elevation difference: how did fish get there and when?)

19th century railroad engineers configured a 5 mile long, 2 inch diameter steel pipeline from Bonanza spring to intersect the proposed route of the rail line. The tiny community of Danby (now a ghost town) was built in 1883 at the end of the pipeline as a water stop on the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad, (760 feet lower in elevation than the spring). By 1887 the rail line between Chicago to Los Angeles was completed, with the Mojave Desert section dependent on piping water from mountain springs such as Bonanza. In the early 20th century the spring supply piped to Danby was augmented by groundwater from wells drilled next to the rail line.

The Bonanza spring story is just one example of how groundwater from wells and springs played an important role in the development of America’s transcontinental rail roads in areas where permanent or seasonal surface water sources were not available for steam locomotive “fill-up” stops.

More information

Spring hydrology: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15275922.2018.1448909

Danby: https://www.trailsendpublishing.com/blog/danby-a-condensed-history

Locomotive water consumption: Water stop – Wikipedia

Picture of the month prepared by Andrew Stone, Hydrogeologist, andrewstone@gmail.com

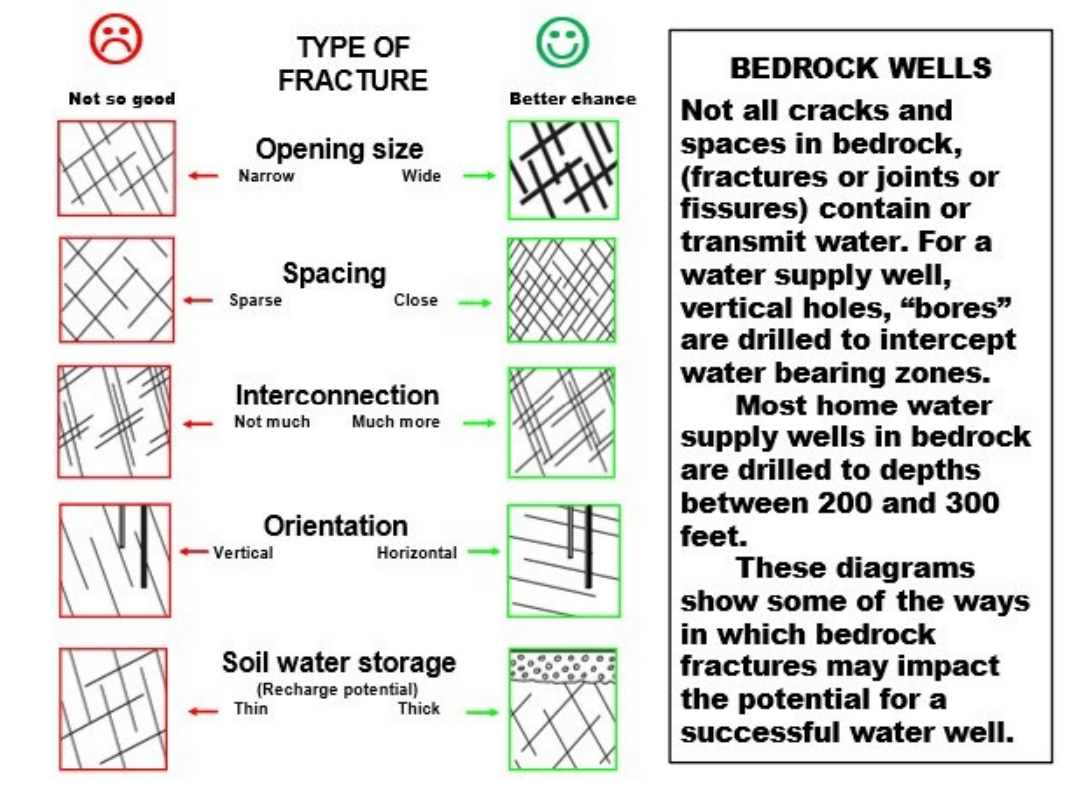

WELLS IN BEDROCK FRACTURES

How often do you get to see a cross-section of what was until very recently a subsurface drill hole intercepting a bedrock fracture?

The photo of 1.4 billion old Silver Plume granite was taken on the I-70 frontage road in Mount Vernon Canyon just west of Golden, Colorado.

Photo Credit: Peter Barkmann, Colorado Geological Survey

The photograph shows a now exposed section view of a drill hole intercepting bedrock fractures in granite bedrock. When occurring below the water table, saturated fractures in bedrock can transmit and store water. To be successful, a bedrock well should intercept saturated fracture systems that are interconnected. In many cases, fracture systems that are connected to recharge zones, such as overlying layers of sediment, have the best chance of producing a reliable sustainable yield. There are millions successful bedrock wells providing water to homes, farms and businesses throughout the USA. Some bedrock wells have limited connection to groundwater and yield may decline seasonally or in times of drought. Aerial imagery and geophysical techniques can be effective in identifying the orientation and density of fractures and optimizing the chances of selecting a site for a successful water well.

Picture of the month prepared by Andrew Stone, Hydrogeologist, (andrewstone @ gmail.com)

THREE ROCK TYPES IN ONE PHOTOGRAPH

1. Dolerite (igneous – intrusive volcanic)

2. Mudstone (sedimentary)

3. Where the dolerite as molten magma “cooked” the sedimentary rock, (metamorphic)

Photo Credit: Andrew Stone

The sedimentary layers in the photograph are in the Beaufort Group of the Karoo Sedimentary Basin in South Africa and were deposited about 250 million years ago. The igneous dolerite dike (1.) resulted from volcanic activity about 180 million years ago. Dikes can serve as barriers or as conduits for groundwater movement. Geophysical techniques are typically used to help characterize the geometry of subsurface geology in areas where dykes and sills occur.

Sill or Dike?

A sill of igneous rock does not cut across preexisting rock beds and is described as concordant. An igneous dike (as shown in the photograph) is described as discordant and does cut across the layers of older rocks.

For links and more information:

The Colorado Groundwater Association has invited Ron Bell, Senior Geophysicist, to be the luncheon speaker for their monthly meeting. On November 14, 2018, Ron will be presenting “Applying Groundwater Geophysics in the Prairies and Mountains of Colorado”. In his discourse, Ron highlights the geophysical data and cost effective benefits of integrating geophysical methods in groundwater resources exploration and how they contribute to the success of the project(s).

Ron has over thirty years of experience in the application of geophysical technology to groundwater, mineral, geothermal, and hydrocarbon resources exploration as well environmental and geotechnical subsurface site characterization. His experience includes the acquisition, processing, visualization, and interpretation of terrestrial, borehole, and airborne potential field data including direct current resistivity, induced polarization, time and frequency domain electromagnetic, magnetic, and gravity methods.

The luncheon will be from 12:00 PM – 1:00 PM

Geotech Environmental Equipment, Inc.

2640 East 40th Ave. Denver, CO 80205.

For more details click here.