In the age of steam locomotives in the US, from the mid 19th to the mid 20th century, water was a critical need. The availability of water from springs was often a determining factor influencing routes of railroads in desert environments. Surveyors seeking water sources often worked years ahead of rail line construction because routes had to follow water availability. Steam locomotives could use up to 150 gallons of water per mile and required frequent stops to “fill-up.”

Bonanza Spring is the largest spring in California’s Mojave Desert. Located in the foothills of the Clipper Mountains it emerges from bedrock as a perched spring disconnected from the basin-fill aquifer systems in the desert valleys hundreds of feet below. The spring is at an elevation of 2,105 feet above sea level. According to historical records, and current measurements, the spring flows at a fairly constant rate of about 10 gallons per minute. In stark contrast to the dry surrounding landscape, vegetation where the spring emerges (photo) includes mesquite, cottonwood trees, and cattails. In addition to serving as a water source for creatures such as desert bighorn sheep, desert tortoises and jackrabbits, the spring is habitat for frogs, toads, catfish and bluegills. (Separated from the nearest permanent surface water sources by many miles and great elevation difference: how did fish get there and when?)

19th century railroad engineers configured a 5 mile long, 2 inch diameter steel pipeline from Bonanza spring to intersect the proposed route of the rail line. The tiny community of Danby (now a ghost town) was built in 1883 at the end of the pipeline as a water stop on the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad, (760 feet lower in elevation than the spring). By 1887 the rail line between Chicago to Los Angeles was completed, with the Mojave Desert section dependent on piping water from mountain springs such as Bonanza. In the early 20th century the spring supply piped to Danby was augmented by groundwater from wells drilled next to the rail line.

The Bonanza spring story is just one example of how groundwater from wells and springs played an important role in the development of America’s transcontinental rail roads in areas where permanent or seasonal surface water sources were not available for steam locomotive “fill-up” stops.

More information

Spring hydrology: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15275922.2018.1448909

Danby: https://www.trailsendpublishing.com/blog/danby-a-condensed-history

Locomotive water consumption: Water stop – Wikipedia

Picture of the month prepared by Andrew Stone, Hydrogeologist, andrewstone@gmail.com

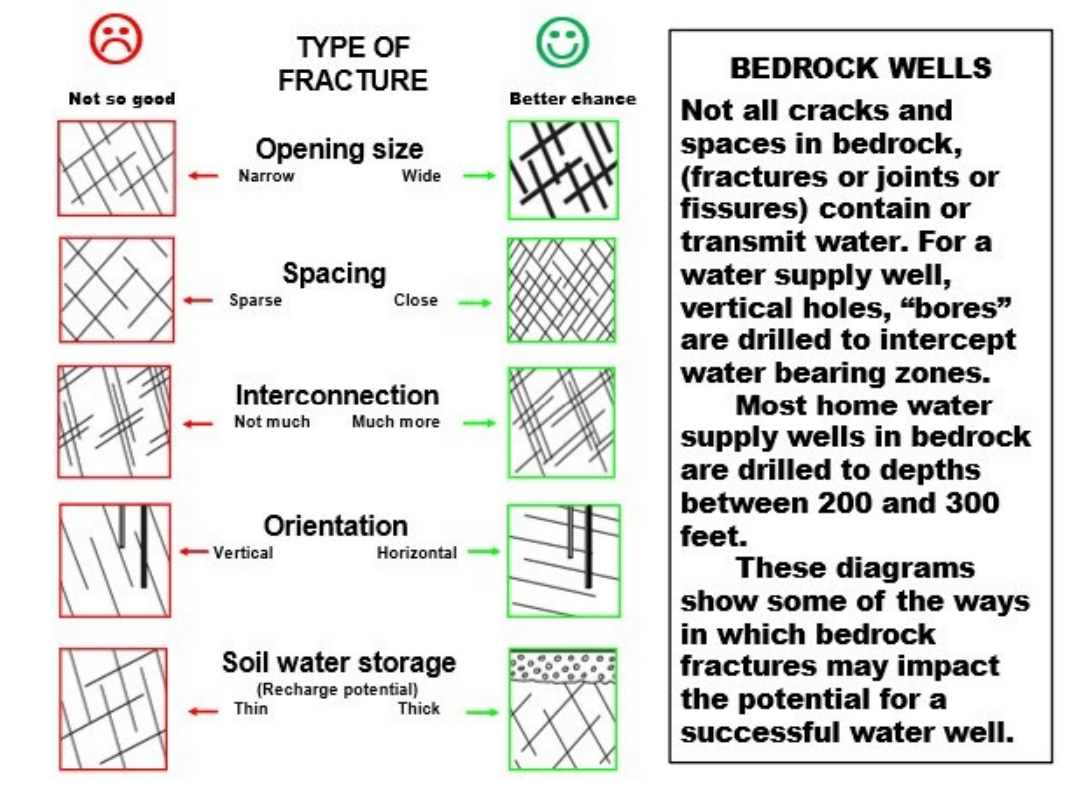

WELLS IN BEDROCK FRACTURES

How often do you get to see a cross-section of what was until very recently a subsurface drill hole intercepting a bedrock fracture?

The photo of 1.4 billion old Silver Plume granite was taken on the I-70 frontage road in Mount Vernon Canyon just west of Golden, Colorado.

Photo Credit: Peter Barkmann, Colorado Geological Survey

The photograph shows a now exposed section view of a drill hole intercepting bedrock fractures in granite bedrock. When occurring below the water table, saturated fractures in bedrock can transmit and store water. To be successful, a bedrock well should intercept saturated fracture systems that are interconnected. In many cases, fracture systems that are connected to recharge zones, such as overlying layers of sediment, have the best chance of producing a reliable sustainable yield. There are millions successful bedrock wells providing water to homes, farms and businesses throughout the USA. Some bedrock wells have limited connection to groundwater and yield may decline seasonally or in times of drought. Aerial imagery and geophysical techniques can be effective in identifying the orientation and density of fractures and optimizing the chances of selecting a site for a successful water well.