May 5, 2025

Picture of the month prepared by Andrew Stone, Hydrogeologist, (andrewstone @ gmail.com)

HAND PUMP WITH NO HANDLE? A LEARNING OPPORTUNITY FOR THE WORLD

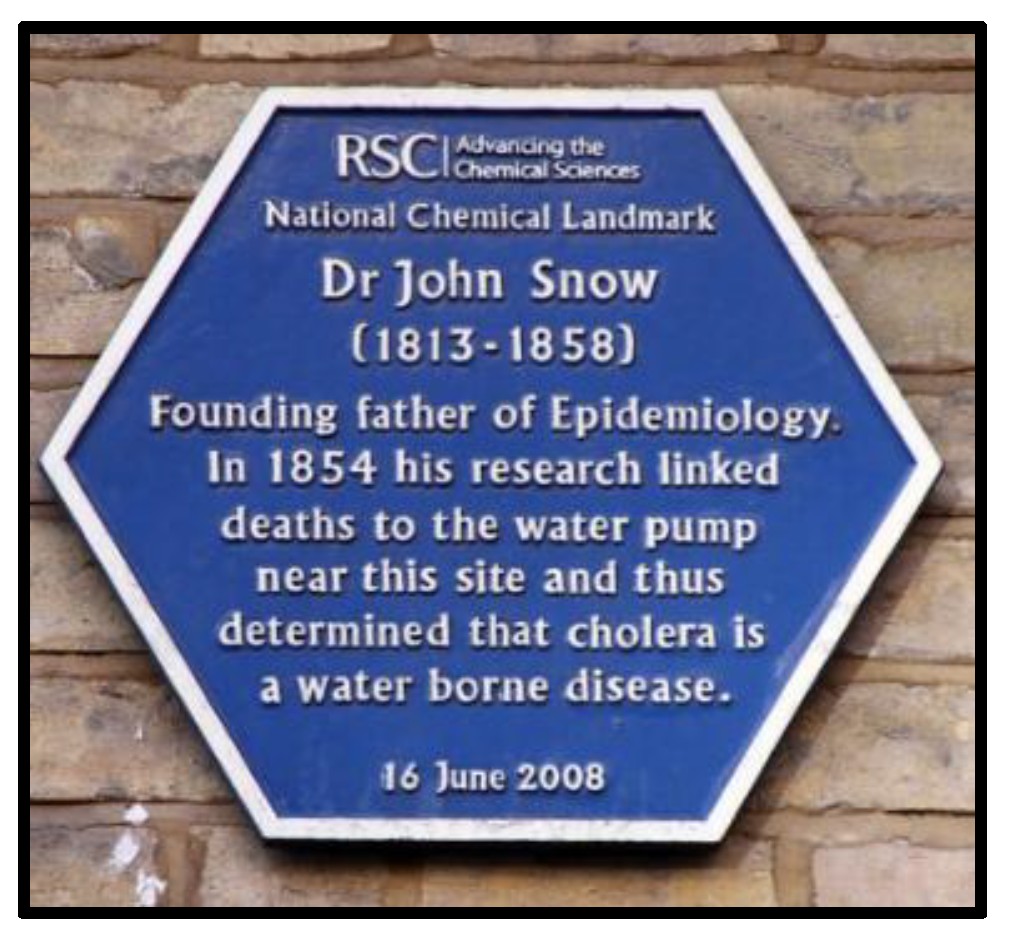

In 1854, in Soho, London – a pump handle was removed from a public water-supply well. Dr. John Snow has entered the history books because his detective work identified the contaminated public well as the source of a cholera outbreak. To prevent further infections, he had the authorities remove the pump handle to stop citizens from using the well.

In the mid 19th century, London, England, was a rapidly growing metropolis of over 2.5 million, with overcrowding, widespread poverty, and lack of sanitary services. With streams and ditches highly polluted, thousands of shallow wells were the only public water supply for many areas of London. Sewer systems were just developing, but cesspits served for most wastewater disposal. Outbeaks of cholera were common. At that time it was thought (incorrectly) that diseases were spread through the foul-smelling air in a process known as miasma.

In introductory classes, today’s students of public health, groundwater and water supply programs worldwide learn about the 1854 cholera outbreak in Soho, where 600 people in a small area died from cholera in just a few days. For groundwater specialists in particular, the case study of the outbreak is a classic lesson in contamination risk. The “detective work” by Dr. Snow who lived near Broad Street, (and who, incidentally, was a physician to Queen Victoria) identified the source of water contamination and the well pump handle was removed to prevent use of the unsafe supply. His work also provided clear evidence that ingesting cholera-contaminated water was the cause of the cholera outbreak, and he helped disprove the theory that miasma caused disease.

Dr Snow and local priest Henry Whitehead mapped homes where people had died. They identified that virtually all the cholera victims used the Broad Street pump for water. People in the same area who accessed different wells or who purchased water from water companies were not affected. Further investigation narrowed the origin of the August 30th outbreak to the death three days earlier, of a cholera infected five-month-old child, Francis Lewis at 40 Broad Street. The baby’s mother had washed the soiled diapers (also known at that time as tailclouts) from the cholera-infected baby and dumped the dirty water in a shallow cesspit. The crumbling cesspit brickwork was found to be just 2 feet 8 inches from the well, with the well water level just 8 feet below.

During the 19th century thousands of dug wells were needed for the rapid growth of London’s population. The geology below London comprises thin layers of sand & gravel, maybe up to 25 feet, overlying 150 to 200 feet of Eocene London Clay below which are aquifers with high quality groundwater in Cretaceous Chalk that underlies the whole London basin. Some of the “safe” water supply identified during the Broad Street cholera outbreak came from private water companies that sourced groundwater from chalk aquifers discharging as springs in Hertfordshire 40 miles north of London. The spring water was delivered to the city by canal and then by hollowed-out elm log pipe systems. That groundwater supply source in Hertfordshire continues to be part of London’s current water supply (but not via hollowed out logs!).

The Broad Street pump story provides us with basic lessons about wellhead protection and the critical importance of investment in urban sewers, water supply systems and properly constructed wells. [It is sad that today, 170+ years later, millions of people endure unsanitary conditions in slums and refugee camps in many parts of the world where the status of sanitation and water supply is reminiscent of London’s 1854 Broad Street.]

More information:

More information: Wikipedia Link

Other Research: Link to interesting research by Dave Boylan about Baby Francis Lewis